Japanese Ceramics & The Art of Sake

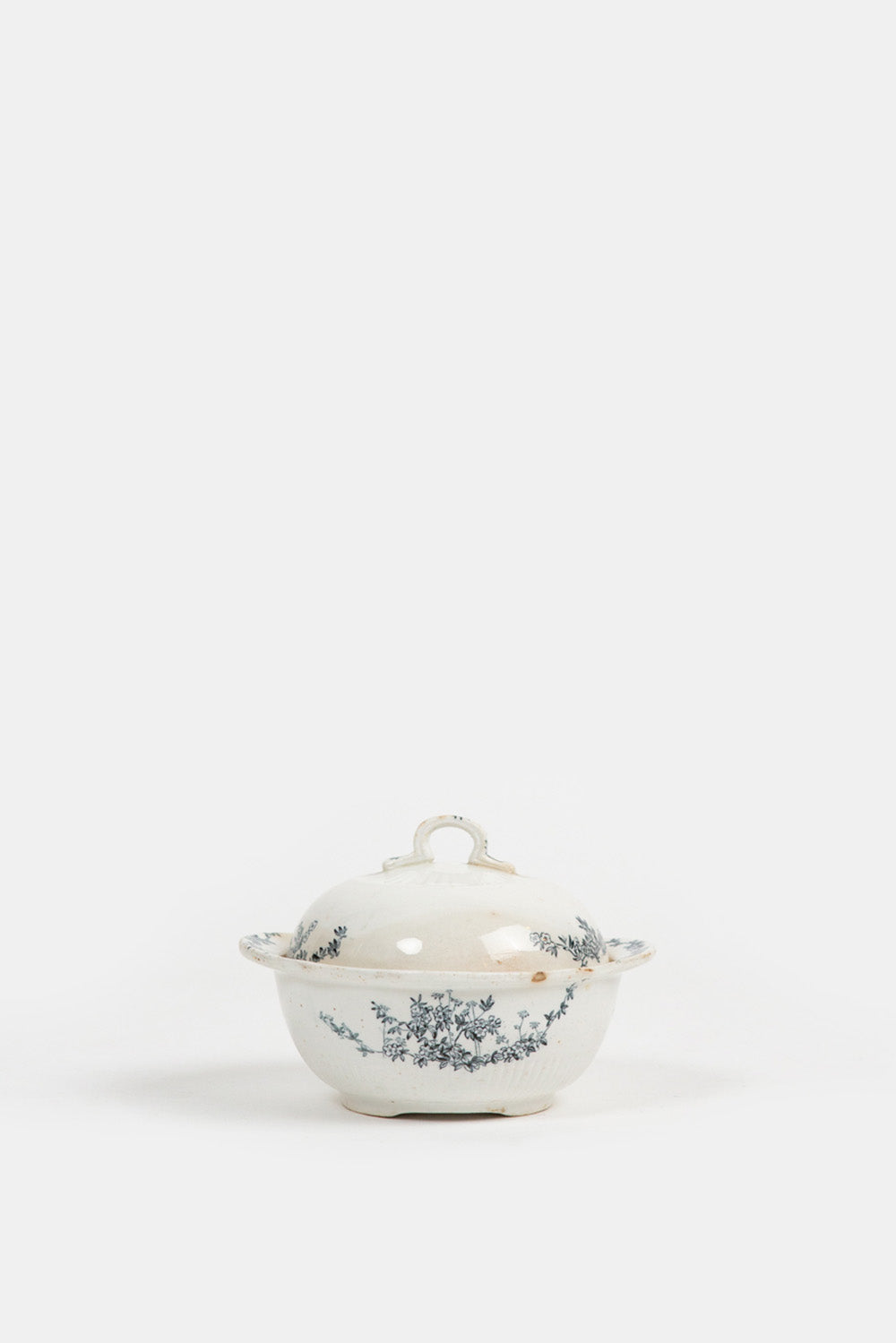

On April 27th of 2024, we were honored to host a diverse exhibition of modest yet extraordinary Japanese ceramics at the Erica Tanov Design Studio and Showroom. This important collection featured works by distinguished Japanese artists of the 20th century — including the Certified Living National Treasures Fujiware Kei, Kato Takuo, and Isezaki Jun — alongside ceramics of understated excellence created by unknown artists. The afternoon of viewing and mingling amongst the objects was accompanied by an enriching, insightful talk by Arjun Gupta, a leading expert in Asian Art & Antiquities and Co-Founder of Worthound.

To share a deeper understanding of the unique cultural heritage of Japanese ceramics, we asked Arjun to compile his April 27th talk into the following. Our many thanks to Arjun for his work and for writing this deeply meaningful text. We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the collector for lending their truly incredible collection to our studio. Our heartfelt thanks also go to Worthhound Co-Founders Martin Gammon and Amy Maniatis for their time, exemplary help, and support to bring this exhibition to life. This collection enables us to look closely at the beauty of seemingly everyday, ordinary objects and tap into the elusively wonderful world of Japanese aesthetics.

Shop the online exhibition of JAPANESE CERAMICS & THE ART OF SAKE here

_________________________________________________

MODERN JAPANESE CERAMICS & THE ART OF SAKE: Meiji through Heisei

Arjun Gupta

Asian Art Specialist & Co-Founder of Worthound.

This collection was acquired over the course of 20 years from Kyoto, Tokoname, Mashiko and Hagi. The collector’s interest in modern Japanese ceramics began with her association with the celebrated ceramicist Paul Solder, who was inspired by the writings of Bernard Leach and Japanese mingei, the 20th century movement of Japanese folk art. Solder began developing his own style of raku ware in the late 1950s, and his experimentation led to the creation of American Raku.

The title of the exhibition, Japanese Ceramics & the Art of Sake: Meiji through Heisei, references several fairly expansive areas of discussion. However, my focus will be the historic context that frames our encounter with these extraordinary, yet ordinary objects - guinomi (sake cups) and tokkuri (sake flasks). This essay offers a brief historical summary, before touching on the aesthetics and cultural resonance these cups and flasks contain.

The subtitle of this exhibition: “Meiji Through Heisei,” describes the span of modern Japan from 1868 - 2019 (including the Taisho and Showa reigns of the 20th century), but I’m going further back, back to the beginning.

The term for the Japanese native ceramic tradition is “yakimono” meaning ”fired” or “burned thing”. These objects of clay and fire have an intimate relationship with the geographic position of Japan, a string of thousands of islands along the volcanic Ring of Fire. It seems fitting then, that their raw, rough forms, and milky, iridescent glazes hold a kind of primordial quality.

In ancient Japan, pottery making was a major industry from the neolithic era up until the 6th century. The name “Jomon” refers to the 15,000 year-long neolithic era in Japan, but its meaning is also a direct reference to the straw rope patterned pottery produced then. It may come as no surprise then that Japan lays claim to the earliest continuous tradition of pottery in the world, with the earliest finds dating from 14,000 BCE.

Interestingly, pottery is barely mentioned in the Kojiki and Nihon shoki, Japan’s earliest texts. There, the creation myth describes the metal mirror, which coaxed the Sun Goddess Amaterasu out of her cave, restoring light to the world. There is also the sword, given by Amaterasu to her grandson who descends to earth becoming the first ruler of Japan and establishing the imperial lineage - one that continues to this day under the 232nd reign of the Reiwa Emperor.

But where is pottery in these early texts? One theory explains that the mirror and sword replaced pottery. After all, pottery predates metal working, which began during the bronze age about 300 BCE - that’s 14,000 years after evidence of pottery production in Japan. I mention this to underscore the unparalleled unbroken longevity of the tradition in Japan.

These earliest texts tell of the founding Emperor Jimu in the 7th century BCE, descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu, and the storm god Susanoo. At this time, Japanese pottery was still primarily unglazed, baked clay. We can consider Japanese pottery, in its earliest phase, as one without glaze, a kind of pure, simple earthenware that remains at the center of the tradition.

During the classical Heian period from the 8th-12th century CE, when Kyoto became the Imperial capital for the next thousand years, pottery production became increasingly stratified with wares for the court and aristocracy, and those for everyone else. Then, during the medieval Muromachi Period in the 14th century, this native tradition absorbed external forms and techniques from China and Korea. At this time, domestic Japanese ceramic artists began experimenting with and creating uniquely Japanese styles represented in the present collection.

In late medieval Japan, we see the emergence of the “Six Ancient Kilns” - each named after six centers of production with their respective styles: Bizen, Echizen, Seto, Tokoname, Shigaraki, and Tanba. Many of the pieces in this collection reflect these lineages. The pattern of foreign influence and the reiteration of qualities more closely associated with Japanese sensibilities and practices continues today with modern Japanese ceramics, which are informed both by native traditions, and techniques and glazes from around the world.

In the instance of these ceramic sake wares, we can trace their forms to the emergence of the Tea Ceremony. This ritual of tea preparation and drinking had probably the greatest single influence on what we consider traditional Japanese aesthetics. It has its roots in the growth of Zen Buddhism during the early medieval period when monks would have formal gatherings before an image of the first Zen patriarch, the Indian monk Bodhidharma. There, the monks would drink tea from the same bowl as a kind of sacrament. This ritual later became secularized under the Ashikaga Shogun, Yoshimitsu, who hosted tea parties on the grounds of his villa Kinkakuji, the famed Golden Pavilion.

No single figure has had as great an impact on traditional Japanese ceramics as the 15th century tea master Sen no Rikyu. In his later years, Rikyu enjoyed the patronage of the feudal lord Oda Nobunaga and then, his influential retainer, the feudal lord Hideyoshi, considered the second great unifier of Japan.

Rikyu’s taste for rustic Japanese ceramics over the polished and expensive Chinese porcelains became increasingly fashionable, along with the ceremony, which took place in simple tea huts whose entrances were designed intentionally as too narrow to enter wearing a sword.

At the heart of Rikyu’s interpretation of the tea ceremony were deceptively simple tea wares. But their aesthetics spread to influence a host of artistic, literary, and architectural forms.

What were these aesthetics? Along with the typically universal principles of harmony, respect, tranquility, and purity, Rikyu was a proponent of the Japanese aesthetics we know as wabi and sabi. These are concepts that seem at odds with the profusion of noise and digital chaos we contend with in our daily lives today, but they are also here nonetheless, under the surface.

Both terms define a particularly Japanese sense of beauty. Wabi is derived from the adjective wabishi meaning wretchedness as opposed to splendor, impoverishment over materialism. It reflects the significance of inner strength and value, rather than an outward dependence on wealth and power. Sabi suggests a preference for the old and faded, it is a kind of nostalgia, and underscores the Buddhist concepts of the impermanence of life and the evanescence of things.

Together, both are embodied in the ceramics we see here - an emphasis on the natural and aged, on asymmetry and austerity, rough and smooth textures thrown together, imperfection where accidents and errors are subsumed in ostensibly spontaneous forms.

While many of us are at least somewhat familiar with wabi and sabi, there is one other concept I want to touch on that binds these aesthetics into form. This is the lesser known, but equally important principle of shibui, which originally described the astringent taste of unripe persimmon - a kind of “sourness” before the sweet. In a broader sense, it came to mean an evolving perfection all around us, but also in the refined understatement of simple ceramic wares, monochrome ink painting, tea and of course, sake!

Drawing on these diverse aesthetic, technical, and historical threads, modern Japanese ceramics offer a unique art form that is, at once, utilitarian, ritual, economic, and cultural. And this breadth and depth of function, in turn reflects an aesthetic vocabulary that is incredibly rich, evoking a vessel’s purpose along with the appropriate setting, the season, and a host of symbolic and formal associations with the worlds of literature, history, and of course, nature.

Finally, I’d like to briefly summarize what I think is particularly interesting about modern Japanese ceramics and their role as an art form in Japanese society today. Unlike the Western notion of art and an economy of art that requires wealth, patrons, and art advisors, in Japan, there is a parallel arts culture supported by everyday people who use affordable and simple objects. These objects have a relatively small high-end market presence. This culture and economy first emerged during the impoverishment of the post-war period, but it continues today with every bubble that bursts and every recession that follows. Modern Japanese ceramics belong in this category of work that is both popular and affordable. In this light, affordability is one of the hallmarks of good ceramics for the Japanese.